The Bad Bargain: Why We Trade Our Dreams to Escape Our Nightmares

In his final book, the late, great, American author, Cormac McCarthy, wrote, “You would give up your dreams in order to escape your nightmares and I would not. I think it’s a bad bargain.”

Like the rare movie you can’t stop thinking about days later (Christopher Nolan’s Memento, for instance) or the song that sticks in your soul (U2’s Bad, Radiohead’s Everything in its Right Place, Kendrick Lamar’s Father Time…take your pick!), I can’t get away from this quote.

I had an experience in the Utah desert a few weeks ago that reminded me of a “bad bargain” scenario that I’d like to share with you in our Financial LIFE Planning read this week—before our in-house investment guru, Tony Welch, is “Stating the Obvious” (which might not be) in this Weekly Market Update.

Thanks for spending a few precious moments of your weekend with us!

Tim

Tim Maurer, CFP®, RLP®

Chief Advisory Officer

In this Net Worthwhile® Weekly you'll find:

Financial LIFE Planning:

Why We Trade Our Dreams To Escape Our Nightmares

NWWW Podcast (Replay):

George Kinder’s Vision For A Fiduciary Society

Quote O' The Week:

Anaïs Nin

Weekly Market Update:

Stating The Obvious

Financial LIFE Planning

The Bad Bargain: Why We Trade Our Dreams To Escape Our Nightmares

One of the most productive meetings I had this year was atypical, to say the very least. I’d driven a total of about seven hours from the Salt Lake City airport into the Utah desert to explore a series of slot canyons with the CEOs of four different businesses. Despite it being largely unstructured time with no agenda, it was very purposeful, even profound.

Already as far into “the middle of nowhere” as I have ever been, we arrived at the most technical of the slot canyons we’d face, where the definition of this mountainous feature crystallized in stark reality. You see, slot canyons are narrow passages carved through sandstone by millennia of flash floods, some sections barely wide enough for a person to squeeze through sideways, with towering walls that block out the sky and create a disorienting sense of enclosure.

In this particular case, we started into a canyon that was skinny enough that we could touch both sides with our hands, but about halfway in, it was so tight that I, the slightest member of our expedition, had to take my small daypack off and turn sideways just to squeeze through to the other side.

It was at this juncture that two of our group confided that they suffered from some degree of claustrophobia. They seriously considered just turning back (especially after spotting a tarantula guarding one of the tight turns). But instead, what had been a group of five individuals exploring this beautiful, if unearthly, setting became a singular unit in pursuit of the objective of encouraging each of its members through this harrowing stretch.

And because you’ve heard many stories like this before, you know they made it. And you likely further know that it became the most memorable moment of the trip.

The Bad Bargain

That’s because we know somewhere deep within what author Cormac McCarthy was capable of putting into words in “The Passenger,” the final novel he published prior to his death in 2023:

“You would give up your dreams in order to escape your nightmares and I would not. I think it’s a bad bargain.”

In how many areas of life have you seen this play out?

Maybe it was a marriage or business partnership that reached a trial that seemed impassable. Perhaps it was an academic or career move that required a level of courage you’d never had to summon to date.

What was the decision that demanded a bolder “Yes” or “No” that you faced? And what did you do?

Comfort’s Cost

We make bad bargains like these all the time, and in our adult lives, all too often, it is financial considerations that are either in the lead or supporting role.

Some structure their entire financial lives around nightmare avoidance—staying in soul-crushing jobs for security, never taking entrepreneurial risks, keeping money in cash because markets are (always) scary, or not retiring for fear that they may run out of money. They’re often trading dreams for the avoidance of nightmares.

Our penchant for comfort in the present is often the very thing that narrows our future.

The Science of Regret

And this intuition is corroborated by many findings, especially from the field of behavioral economics. Kahneman and Tversky demonstrated that losing feels twice as bad as winning does good, while Gilovich and Medvec found that choosing to take action in the short term may cause more pain, but inactions are regretted more in the long run.

When taking a retrospective view of our lives, our biggest regrets tend to involve things that we failed to do or pursue. The paths not taken.

But, even when we take the risk and it results in an apparent loss, we can still win, as the persistent pursuit of hard things builds resilience, transforming courage into a core competency.

My two claustrophobic companions didn’t just survive that slot canyon—they emerged different. Stronger. Not despite the fear, but because of it.

This is the paradox: the thing that feels safest in the moment—turning back, playing defense, avoiding the squeeze—is often the choice we’ll regret for years. That’s why McCarthy’s words ring so true: You can give up your dreams to escape your nightmares, but it’s a bad bargain.

This post was initially published on Forbes.com.

NWWW Podcast (Replay)

In case you missed it last week, I had a fascinating conversation with one of the leading voices of the fiduciary movement, George Kinder, who’d like to see the notion of fiduciary spread beyond financial advisory firms to, well, the whole world.

Quote O' The Week

Anaïs Nin (1903-1977) was a French-Cuban-American diarist and novelist whose fearless, decades-long journals made her a literary icon of personal transformation and creative courage.

Weekly Market Update

Most markets were slightly down this week. Let’s hope Tony tells us why:

- 1.63% .SPX (500 U.S. large companies)

- 0.07% IWD (U.S. large value companies)

- 1.88% IWM (U.S. small companies)

- 0.76% IWN (U.S. small value companies)

+ 0.94% EFV (International value companies)

- 0.85% SCZ (International small companies)

- 0.13% VGIT (U.S. intermediate-term Treasury bonds

Stating The Obvious

Contributed by Tony Welch, CFA®, CFP®, CMT, Chief Investment Officer, SignatureFD

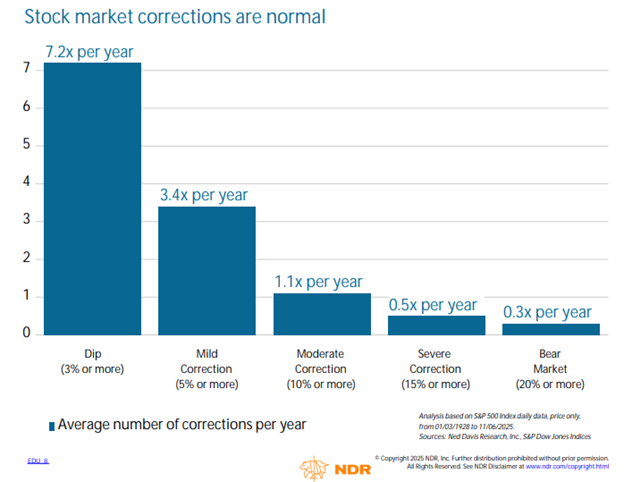

Last week, we received a few concerned inquiries over some articles that referenced relatively elevated valuations and the CEOs of Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley warning of a 10-20% correction in the next year or two. That may sound ominous, but when we consider that an average year does, in fact, include a 10% correction, I’m not so sure that is going out on much of a limb. As the chart below shows, on average 5% corrections have happened over three times per year, 10% corrections over once per year, and 20% bear markets have occurred about once every three years.

We agree that valuations are pretty rich, but the process of correcting and then rallying is a pattern as old as the stock market itself. Importantly, Ted Pick, CEO of Morgan Stanley, also called these corrections a healthy development, to which we agree. A 10%+ correction tends to reset investor sentiment, setting a base for the next leg higher. Is it fun to watch your account balances correct double-digits? Of course not. But we hold stocks for long-term growth, not for near-term spending needs. If we know that we should expect one of these corrections at least once a year helps to arm us with the ability to normalize it and stay the course.

Chart O’ The Week

The Message from Our Indicators

Economic data continues to show an economy that’s expanding, though more slowly than earlier in the year. The ISM Manufacturing PMI slipped again in October, pointing to softer growth in factory activity, while the S&P Global measure remained in modest expansion. Taken together, the message is that production is cooling but not contracting.

The labor market tells a similar story. Payroll growth has slowed, and layoff announcements have climbed to their highest level in several years. Job openings have fallen since late summer, but initial unemployment claims remain low. Overall, hiring demand is easing, not collapsing, a sign that the economy is downshifting rather than stalling. As we think about 2026, there is important support coming online in the form of greater tax refunds and a lower Fed funds rate.

Corporate fundamentals remain solid. Companies have managed to protect margins even as input costs have risen, and many still have pricing power. Investment spending outside of AI remains subdued, though recent lending data and survey results suggest capital spending could be stabilizing. The One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA) should add to that momentum next year, helping support domestic manufacturing and infrastructure investment.

Markets are reflecting this mix of cooling data and policy optimism. Treasury yields have stabilized in the low 4% range, and equities remain resilient as investors look ahead to potential fiscal stimulus in 2026. Overall, our indicators point to an economy that is losing a bit of altitude but still on course, slowing for now, yet with the potential to pick up speed again as policy support takes hold. We continue to give the bull market the benefit of the doubt, but have our eyes on the job market, bank liquidity, and consumer confidence to warn of trouble ahead. These variables have deteriorated but not to recessionary levels.

Now let’s get outside and enjoy the last of leaf-changing season!

Tim