The Narrow Path: Why Choosing Hard Things Is Your Best Investment

Yes, personal finance is more personal than finance…but this week’s post is one of the most personal I’ve shared in just shy of 15 years writing for Forbes, on what a father can learn from his sons and why voluntary discomfort—from marathons to cold plunges to career risks—builds neurological resilience, autonomy, and meaning. Among other things.

Our resident market expert, Tony Welch, is also back fresh off of his family cruise to enlighten us on the markets’ week behind and what we can expect ahead.

Thanks, as always, for joining us and choosing to spend a few moments of your precious weekend with the Net Worthwhile Weekly. We sincerely hope you’re better for it. That is, after all, why we do this!

Tim

Tim Maurer, CFP®, RLP®

Chief Advisory Officer

In this Net Worthwhile® Weekly you'll find:

Financial LIFE Planning:

The Narrow Path: Why Choosing Hard Things Is Your Best Investment

Quote O' The Week:

C. S. Lewis

Weekly Market Update:

Help Is On The Way

Financial LIFE Planning

Why Choosing Hard Things Is Your Best Investment

There are few things in this world that I enjoy more than observing my sons outshine their father. And I’m not just talking about outperforming me at their ages, 21 and 19; that would be an easy task, because at their ages, I was only excelling at what some of my teachers referred to as “untapped potential,” when they were kind, or “underachievement,” when they were honest.

No, the younger is already smarter than I ever was or will be, and more importantly, he has such a heart for true Justice that I’m often in awe of his perspective. His elder brother, meanwhile, possesses a downright eerie EQ that has been so exceptional since a very young age that he has taught me more about empathy and compassion than anyone else, or any of the many books I’ve had to read on the topic, to be a functioning human being.

He also has a trait that I seek to emulate that I’m inclined to share with you today and implore you to consider exercising: the pursuit of hard things.

For example, at the age of 13, he chose to switch sports, from baseball, where he had grown to excel, to lacrosse. For those of you who’ve been cursed blessed to encounter the world of competitive youth sports, and especially lacrosse, you know that this is generally considered too late. I cautioned my son that if he were to make the switch, he’d have to work much harder than the other kids, just to bring his skills to the point of competent, much less competitive. He did.

His hard work paid off many times over, making teams that seemed beyond his reach, captaining his state championship high school team, and earning the opportunity to play college lacrosse at a solid Division II school, despite being undersized. After his freshman year, his coach told him that he was excelling at every phase of the game—footwork, stick skills, “lacrosse IQ”—but the one that is the most challenging to overcome is his size.

Coach challenged him to put an additional 20 pounds of muscle on his 150-pound frame over the summer, and he did, with the help of my wife’s 6,000-calorie-per-day diet and lifts so heavy they’d have put me in the hospital.

Then, he made an even harder decision: to leave his sport, his team and his school, recognizing that in order to excel in his chosen major, he’d need to double down on his studies, internships, work in his field, and do it at a school that had an even better ranking for his major, the University of Georgia (Go ‘dawgs!).

But with the peak competitive push of collegiate sports behind him, he purposed himself to pursue something that would be his most challenging physical and psychological feat yet—running a marathon. As a non-runner, this was challenging enough, but he also decided he wanted his first to be a sub-four-hour time. Why not? So, with ChatGPT as his only training partner, he did the work, and I was able to see him cross the finish line on a muggy August morning in Atlanta, where his time read three hours and 58 minutes.

His sense of satisfaction lasted no more than two hours, and within two days, he’d already began training for some crazy weightlifting / running combo competition that takes place the first weekend in November.

So, what does he get out of this persistent pursuit of higher performance—of choosing to do the harder (and harder) thing—and what can we? And why not?

Why—And Why Not—Push Out Of Our Comfort Zone?

1. Not for toughness, but for adaptability

I don’t think there’s any inherent virtue in “being tough” any more than there is in being physically attractive, but choosing discomfort rewires our relationship with fear and increases our neurological resilience.

When we voluntarily choose difficulty, we’re engaging in what neuroscientists call “stress inoculation.” Controlled exposure to discomfort (cold plunges, running when you’re exhausted, even knowingly navigating financial uncertainty) activates the sympathetic nervous system—but because we chose it, we simultaneously engage the prefrontal cortex, which regulates emotional response. Over time, this builds what researchers call “distress tolerance,” as the brain literally rewires to interpret challenge as manageable rather than catastrophic.

For example, three to four times every week, I subject myself to five minutes of discomfort via a cold plunge—an inflatable tub in my basement that is set to 41 degrees. As I told my friend whose expertise is in learning and development, among other things, “Dude, it doesn’t get any easier! The first two minutes, in particular, are pure torture, and I need to talk myself into it every single time.”

“Yup, that’s how it’s supposed to work,” he retorts, before going on to explain the benefits of triggering cold-shock proteins (with an emphasis on the work shock), the release of dopamine that lasts for hours, and the cardiovascular benefits that have helped me reduce the severity and frequency of chronic migraines more than any drug or neurological regimen I’ve tried in 30 years.

The Stoics called this premeditatio malorum—the premeditation of adversity. By choosing hard things voluntarily, we remove fear’s greatest weapon: surprise. You’re not building “toughness” as some macho badge. You’re building optionality. When life inevitably delivers involuntary hardship (illness, job loss, grief), your brain has evidence that you can handle discomfort—because you’ve been practicing.

In essence, choosing to do hard things repetitively cultivates a core competency of doing more hard things. Because, in case you haven’t noticed, life doesn’t actually get easier; we just get better at it.

2. Not for achievement, but for autonomy

Achievement for achievement’s sake tends to ring hollow. You’ve heard all the stories—stories that frankly don’t seem believable—about Super Bowl winners and Olympic athletes who, mere moments after their crowning achievements, tend to experience a hyperbolic erosion of satisfaction (called hedonic adaptation).

But that doesn’t mean nothing has been gained from said achievement. Far beyond the free trip to Disney World and the hardware, the voluntary pursuit of hardship restores agency in an overstimulated world.

Our modern environment is designed to eliminate friction. Algorithms predict what we want before we know we want it. One-click purchasing. Doom scrolling. The result? A dopamine system in chaos. Neuroscientist Andrew Huberman’s research shows that when we get rewards without effort, our baseline dopamine drops—meaning we need more stimulation to feel less satisfied.

But when we choose hard things, especially hard things without guaranteed rewards, we restore what’s called “dopamine baseline.” The effort itself becomes the reward signal.

Psychotherapist and author, Viktor Frankl (who survived Auschwitz), for example, understood that meaning doesn’t come from avoiding suffering—it comes from choosing our relationship to it. In Man’s Search for Meaning, Frankl writes: “Between stimulus and response there is a space. In that space is our power to choose our response.”

I’ve been so inspired by two financial advisors I’ve had the privilege to coach this year, each of whom chose to leave stable, rewarding jobs with plentiful personal and financial rewards, simply because those environments provided them with less agency than the more entrepreneurial paths, the veritable restart they’ve chosen instead.

It’s because they know that uncertainty chosen freely is psychologically different from financial uncertainty imposed upon you. This isn’t semantics; it’s the difference between agency and victimhood.

3. Not for self-improvement, but for self-forgetting

Here’s where we really dive into some nuance neuroscience, because the optimal end of choosing hard things isn’t to post it on the ‘Gram and the momentary dopamine hits from a handful of distant likes. It’s because the choice of discomfort dissolves the illusion of separation.

(Huh?)

There’s emerging research in contemplative neuroscience showing that intense physical challenges (endurance sports, cold exposure, breathwork) temporarily quiet the default mode network (DMN)—the part of the brain responsible for self-referential thinking, rumination, and the sense of being a separate self.

When the DMN quiets, people report feelings of interconnection, present-moment awareness, and what psychologists call “self-transcendence.” This isn’t woo-woo pop psychology—it shows up on fMRI scans. The brain stops narrating the story of “me” and starts directly experiencing a more present reality.

Every wisdom tradition has a version of this: the ego is an illusion maintained by comfort. Buddhism calls it dukkha—the suffering that comes from clinging to a false sense of a permanent, separate self. Christian mystics practiced asceticism as a path to personal growth. Indigenous rites of passage involved physical ordeal.

Why? Because when you’re at mile 23 of a marathon, or 90 seconds into ice water, or staring at a spreadsheet showing zero revenue for month three of your new business venture—the mental chatter stops. You’re not rehearsing the past or anxious about the future. You’re just here, in your body, in what is referred to as a flow state.

The real gift of voluntary hardship isn’t that you “accomplish” something, therefore, but that you get brief moments of relief from the exhausting job of being “you.” The self-improvement industrial complex has it backward: we don’t choose hard things to become better versions of ourselves (although that’s a likely result). We choose them to occasionally escape the tyranny of selfhood altogether.

The Narrow Path

The question isn’t whether you should choose hard things. Life will choose them for you eventually, through illness, loss, economic upheaval, or the entropy of aging. The question is whether you’ll practice first, while you still have the luxury of choosing which hard things, and when.

You don’t need to run a marathon or start a business or plunge into ice water. But you probably know what your hard thing is. It’s the one you’ve been avoiding because it’s uncomfortable, uncertain, or inconvenient. It’s the conversation you’re not having. The investment you’re not making (in your portfolio or yourself). The risk you’re not taking because the safe path is so much easier.

The narrow path isn’t narrow because few people can walk it. It’s narrow because few people choose to.

What if you did?

This post was initially published on Forbes.com.

Quote O' The Week

C. S. Lewis was a sharp-witted Oxford scholar and cultural critic who explored the deepest human motives—often exposing our blind spots with unsettling clarity.

There is no fault which makes a man more unpopular, and no fault which we are more unconscious of in ourselves; and the more we have it ourselves, the more we dislike it in others. The vice I am talking of is Pride or Self-Conceit.

Weekly Market Update

Would you believe that every one of the indices we’re tracking were up this week? And all the stock-oriented markers were at 52-week highs to finish the week:

+ 1.09% .SPX (500 U.S. large companies)

+ 0.98% IWD (U.S. large value companies)

+ 1.86% IWM (U.S. small companies)

+ 1.57% IWN (U.S. small value companies)

+ 1.76% EFV (International value companies)

+ 1.98% SCZ (International small companies)

+ 0.03% VGIT (U.S. intermediate-term Treasury bonds

Help Is On The Way

Contributed by Tony Welch, CFA®, CFP®, CMT, Chief Investment Officer, SignatureFD

In the next section, we highlight the labor market and some signs of deterioration. We expect slower economic growth in Q4, largely due to the challenging job market. But the potential good news is that help for consumers is on the way in 2026, both in the form of a lower Fed policy rate, and also, from the increase in tax refunds following the passage of the OBBBA.

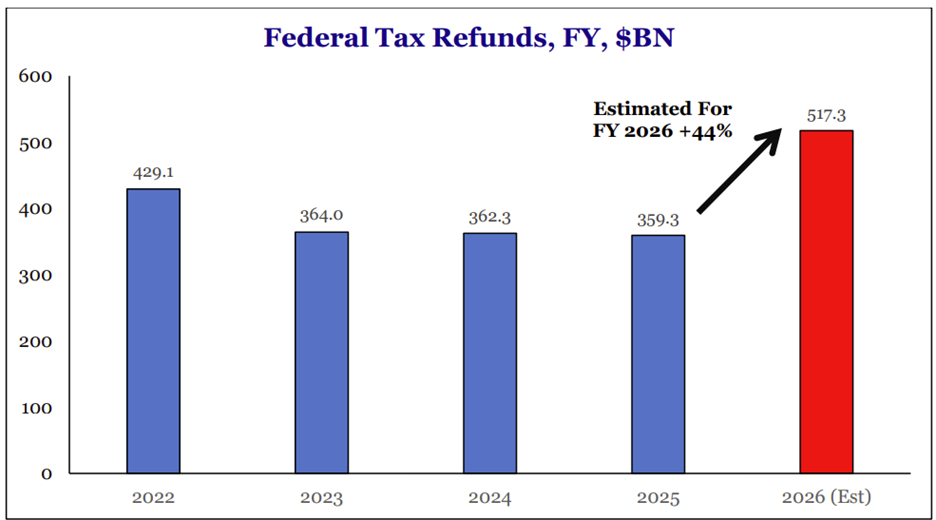

The chart below shows an estimated 44% increase in refunds from this year. The jump equates to roughly $1000 extra per worker. And history suggests that workers tend to spend, rather than save, their refunds. This implies that we could see a pickup in activity in 2026, following a more sluggish Q4.

Chart O’ The Week

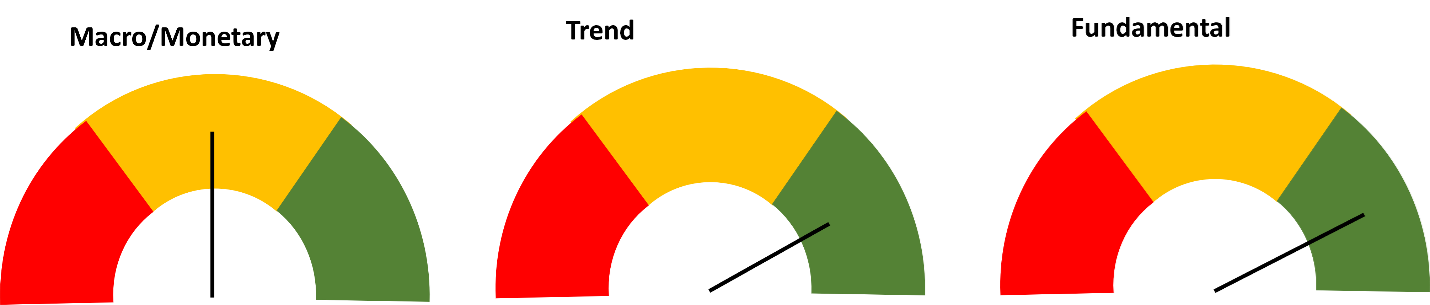

The Message from Our Indicators

Labor market data took center stage this week, but ironically, the most important release isn’t coming. With the government shutdown, the BLS Employment Situation Report has been delayed, leaving investors and policymakers without the usual read on job creation, unemployment, and participation rates. That doesn’t mean we’re entirely flying blind. Private sector data from ADP and Revelio Labs offer some insight into employment trends, and both have pointed to weaker job creation in recent months.

Additionally, consumer confidence surveys show rising concerns about job availability, with more than one-fifth of consumers now saying jobs are “hard to get,” the highest since early 2021. The Chicago Fed’s real-time unemployment rate nowcast has also been drifting higher, and ADP payroll data have recorded back-to-back months of private sector job losses. Together, these alternative indicators suggest labor market slack is increasing, even if we lack the official confirmation. Until the shutdown ends, this patchwork of private data and real-time indicators will shape market perceptions of the employment backdrop.

From a fundamental perspective, a divergence has opened up between broad-based corporate profits and S&P 500 earnings. NIPA corporate profits, a wider measure that includes public and private firms, have posted back-to-back year-over-year declines for the first time this cycle, while S&P 500 earnings have grown at double-digit rates. Historically, NIPA profits tend to lead S&P 500 EPS by one to two quarters, which could imply some downside to forward earnings estimates if the divergence persists.

That said, we expect earnings are likely to grow in upcoming quarters, just at a slower rate. Another market concern has been valuation, but there are some important offsets that explain today’s higher valuation level. The composition of the S&P 500 has shifted meaningfully toward higher-margin, higher-multiple Technology companies over the past two decades. Tech’s share of the index has risen from ~10% in the 1970s to more than 25% today, while lower-multiple sectors like Energy and Staples have declined substantially. We believe this changing mix likely supports a structurally higher “steady-state” valuation multiple for the index than in prior eras, which helps explain why today’s forward P/E near 23×, while elevated relative to history, may be more sustainable than past extremes.

Finally, market action itself has been constructive. Last week, Ned Davis Research upgraded their equity allocation, citing improving seasonal tendencies into Q4 and a positive signal from their primary asset allocation model, which now recommends an overweight allocation in equities. They raised their equity allocation from marketweight to overweight, noting that while sentiment remains complacent and breadth indicators have not yet fully confirmed, seasonal tailwinds and technical strength support the upgrade. U.S. equities are coming off one of their strongest third quarters in years, with the S&P 500 gaining 8% and broad-based strength across sectors and regions.

Seasonality also tilts in favor of equities in the final quarter of the year, particularly in years that followed double-digit drawdowns earlier in the same year. Despite softening employment data, our indicators remain constructive and we continue to give the bull market the benefit of the doubt.

Next weekend, the Weekly’s editor will be enjoying some quality time with his bride and unable to publish a new edition, but we look forward to being with you the weekend to follow!

Tim